Full English text: below.

“Forse King Kong non regge più di tanto nella sua modestia spettacolare e nei limiti oggettivi della sua artisticità a interpretazioni sociologiche o psicanalitiche, ideologiche o politiche. Ma certo la forza eversiva della grande scimmia come modello di alterità rispetto alla società americana del tempo, e più in generale del costume sociale e morale degli anni Trenta, risulta ancor oggi vincente”.

Così scriveva il critico Gianni Rondolino su La Stampa (14 febbraio 1993), in una rilettura delle implicazioni del celebre film del 1933 che, probabilmente, ha centrato il bersaglio ben oltre le aspettative del suo autore.

La trama è certamente ben nota a chi legge, ed è stata riproposta più o meno fedelmente nei successivi remake del 1976 e del 2005; se volessimo però enucleare gli elementi che più la caratterizzano dal punto di vista biologico, questa si potrebbe riassumere in tre punti fondamentali:

un’isola remota, una scimmia gigante, la passione che nutre nei confronti della bionda rappresentante di un’altra specie (l’attricetta un po’ sfigata, Ann Darrow).

Ed è qui che la “forza eversiva” del gorillone ideato da Merian Cooper ed Ernest Shoedsack sembra insidiare quei pregiudizi anti-evoluzionistici largamente diffusi nella società americana del tempo (e, purtroppo, anche in quella attuale).

In tutti e tre i punti, infatti, si ravvisa l’eco di quell’intensa avventura scientifica e intellettuale che, soprattutto durante la seconda metà del XIX secolo, ha accostato eminenti biologi allo studio delle isole quale chiave di lettura privilegiata per decifrare e interpretare i complessi meccanismi alla base dell’evoluzione dei viventi. Island naturalists, per antonomasia, erano Charles Darwin e Alfred Wallace: il primo, tra i numerosi argomenti che confluiranno nell’“Origine delle specie”, annovera le suggestioni ricavate nel corso di una visita alle Galápagos, sulle quali mediterà per lunghi anni; il secondo intuirà l’esistenza di un rapporto tra la diversificazione della vita e la selezione mentre lotta per la propria sopravvivenza in una capanna sull’isola di Ternate, nell’arcipelago delle Molucche. Specialmente Wallace dedicherà grande attenzione al tema dell’insularità, pubblicando nel 1880 “Island life”, opera fondamentale della letteratura biogeografica ottocentesca.

Alfred Wallace nell’isola di Ternate

(Evstafieff/Down House, Downe, Kent, UK/English Heritage Photo Library/Bridgeman)

Grazie al lavoro di Darwin, di Wallace e di altri evoluzionisti (Hooker, Huxley, Lyell, Gray), è stato possibile mettere in evidenza il ruolo di “rifugio” assolto dalle isole, dove faune e flore ormai altrove scomparse per effetto di processi di competizione ed estinzione seguitano a sopravvivere indisturbate.

©Frans Lanting

Gli esempi sarebbero infiniti: i tuatara (Sphenodon), veri e propri “fossili viventi” che si trovano esclusivamente in alcune isolette satelliti delle due grandi isole della Nuova Zelanda; il tilacino (Thylacinus cynocephalus), un carnivoro marsupiale scomparso migliaia di anni fa in Australia ma che fino agli anni Trenta del XX secolo sopravviveva ancora in Tasmania; o, per non andare troppo lontano, la lucertola delle Eolie (Podarcis raffonei), che ha potuto sottrarsi all’estinzione grazie all’isolamento su uno sparuto numero di isolotti dell’arcipelago, mentre la lucertola campestre si andava prepotentemente affermando nelle isole maggiori a discapito della congenere.

Skull Island, dove approdano lo spregiudicato Carl Denham, la povera Ann e il loro seguito, tra le nebbie tropicali non nasconde soltanto il peloso protagonista della pellicola, ma una lunga teoria di ferocissimi stegosauri, tirannosauri, elasmosauri che – evidentemente – non sospettano minimamente di essere gli ultimi superstiti della grande estinzione di massa avvenuta una sessantina di milioni di anni fa.

King Kong.

Alle spalle dei nostri eroi incombe lo Stegosauro.

Anche le dimensioni di King Kong sembrano frutto di suggestioni indotte dagli studi sull’insularità e sui peculiari fenomeni biologici ed evolutivi che la caratterizzano. Se è vero che la definizione di island rule sarà formalizzata da Foster soltanto nel 1964, il fatto che molte specie nelle isole presentassero la curiosa tendenza a “invertire” la taglia (quelle piccole assumevano grandi dimensioni, e viceversa) era ben noto già da parecchio tempo.

Nel 1867 il paleontologo George Busk aveva descritto come Elephas falconeri gli elefanti nani che abitavano Malta, la Sicilia e altre isole mediterranee ancora fino a poche migliaia di anni fa, e che rappresentano uno dei più significativi esempi di nanismo insulare. Nello stesso periodo venivano studiati i resti di uccelli come i moa (Dinornithidae) della Nuova Zelanda o gli Aepyornis del Madagascar, che potevano raggiungere dimensioni impressionanti (fino a 3 metri di altezza) e che – insieme alle testuggini delle Galápagos e di altre isole dell’Oceano Indiano – costituiscono i più celebri esempi di gigantismo insulare.

In realtà, stando alla “regola” di Foster, King Kong avrebbe dovuto essere una scimmia nana, ma pazienza.

L’idea dello scimmione gigante, a quanto pare, sovvenne a Cooper sull’onda emotiva dell’arrivo nello zoo del Bronx di due draghi di Komodo (Varanus komodoensis), catturati da William Douglas Burden durante una missione nelle isole della Sonda, e dei racconti dello stesso Burden, che durante la pericolosa spedizione era stato accompagnato dalla moglie.

Dagli archivi del National Geographic

Una loro fedele riproposizione, tuttavia, non avrebbe avuto facile presa sul pubblico. Così, all’inquietante ma poco espressivo lucertolone venne preferito un animale decisamente più affine alla nostra specie: la scimmia. Chi altri avrebbe infatti potuto rendere credibile la passione per la sventurata Ann, se non qualcuno le cui espressioni non si discostano molto – tutto sommato – da quelle che potremmo cogliere nello sguardo e nel volto di uno spasimante?

Anche in questo caso, non è superfluo osservare che l’accostamento uomo-scimmia sia stato “sdoganato” ben prima della realizzazione della pellicola; se volessimo fissare una data ideale, potremmo farla risalire al 1871, quando Charles Darwin pubblica “The descent of man” e, per la prima volta, affronta con chiarezza i rapporti evolutivi con i nostri cugini più stretti. Questa tesi verrà perfezionata in alcuni suoi aspetti nella successiva pubblicazione di “The expression of emotions in man and animals”, ma lo scienziato inglese era già divenuto il bersaglio degli strali di chi riconosceva nella “discendenza dalle scimmie” un attacco mortale al dogma religioso. Comincia così una lunga contrapposizione tra darwinisti e anti-darwinisti, destinata a proseguire fino ai nostri e che, molto spesso, valicherà i confini del dibattito scientifico.

Alcune caricature di Darwin:

a sx. e a dx. in alto tratte dalla rivista La Petite Lune (fine ‘800);

a dx in basso un’opera recente ©Klaas Op De Beéck

Chissà cosa avrebbe potuto pensare Darwin davanti alle scene dove King Kong lancia languide occhiate alla sua bionda preda, o dove tenta di spogliarla, incuriosito dalla sua carnagione pallida o, probabilmente, dal suo aspetto insolitamente glabro. Per la grande scimmia, Ann non è un giocattolo, un ninnolo con cui ornare la propria caverna: Kong lotta per lei come potrebbe fare soltanto un eroe romantico spinto da un afflato amoroso, o piuttosto – considerando il soggetto – da un’incontenibile pulsione erotica, ancorché non traducibile – per ovvie ragioni – in qualcosa di diverso dalla contemplazione.

Il fatto che una scimmia arcaica sia tanto attratta da un’attricetta hollywoodiana appare come un’implicita ammissione della modesta distanza che, in termini filogenetici, separa le due specie; in qualche modo, sembra alludere a un comune denominatore, o rievocare un antenato condiviso.

Il fatto che una scimmia arcaica sia tanto attratta da un’attricetta hollywoodiana appare come un’implicita ammissione della modesta distanza che, in termini filogenetici, separa le due specie; in qualche modo, sembra alludere a un comune denominatore, o rievocare un antenato condiviso.

Che tale ammissione divenga esplicita in un’opera cinematografica americana degli anni Trenta, però, risulta sorprendente. Nel 1925, infatti, il Tennessee Butler Act aveva bandito l’insegnamento delle tesi evoluzionistiche di Darwin dalle scuole pubbliche degli Stati Uniti; l’argomento tornerà nei libri di testo soltanto nel 1958, ma per effetto del Lousiana Science Education Act del 2008 i programmi scolastici dovranno trattarlo in maniera paritaria al creazionismo, e finiranno per includere anche posizioni negazioniste in merito ad argomenti come l’influenza dell’uomo nel riscaldamento globale.

Al di là di una ristretta élite impegnata nel progresso delle conoscenze scientifiche, la maggior parte degli statunitensi brancola nel buio della beata convinzione che l’evoluzione sia un artefatto demoniaco: secondo un sondaggio Gallup realizzato nel 2012, il 46% degli americani ritiene che l’uomo sia stato creato da un intervento divino intorno a 10000 anni fa. Soltanto il 5% degli elettori del partito repubblicano crede che l’evoluzione si sia verificata senza la guida di dio, mentre la percentuale sale al 19% tra quelli del partito democratico, ed è una ben magra consolazione.

Questa preoccupante istantanea riguarda quello che comunemente viene indicato come il paese più avanzato del mondo sotto il profilo tecnologico e scientifico, dove è però evidente che una grande massa seguiti ad ignorare – quando non addirittura osteggi animosamente – uno dei cardini del pensiero moderno: l’evoluzione.

Potremmo dunque concludere che King Kong riflette alcuni fondamenti delle scoperte scientifiche a supporto delle tesi darwiniste, ma sembra averle assimilate – e restituite al pubblico – in maniera assolutamente inconsapevole. Richiamandoci ancora a Rondolino, la sua “forza eversiva” non viene colta appieno, e il film riuscirà pertanto a superare indenne il severo giudizio dei creazionisti e dei negazionisti, sempre pronti a difendere il dogma dalle pericolose insidie delle evidenze scientifiche. Forse perché, in questo caso, si aggirano sotto le spoglie di uno scimmione un po’ grottesco, un incubo dal quale i prodi aviatori sapranno liberarci mentre si agita disperatamente in cima all’Empire State Building, prima di deporre delicatamente Ann sul cornicione e di precipitare nel vuoto. E mentre Kong spira, ucciso dalla bellezza (come chiosa Carl Denham), Ann è già tra le braccia di Jack, indugiando in tiepidi sospiri: la selezione sessuale ha vinto anche questa volta!

Potremmo dunque concludere che King Kong riflette alcuni fondamenti delle scoperte scientifiche a supporto delle tesi darwiniste, ma sembra averle assimilate – e restituite al pubblico – in maniera assolutamente inconsapevole. Richiamandoci ancora a Rondolino, la sua “forza eversiva” non viene colta appieno, e il film riuscirà pertanto a superare indenne il severo giudizio dei creazionisti e dei negazionisti, sempre pronti a difendere il dogma dalle pericolose insidie delle evidenze scientifiche. Forse perché, in questo caso, si aggirano sotto le spoglie di uno scimmione un po’ grottesco, un incubo dal quale i prodi aviatori sapranno liberarci mentre si agita disperatamente in cima all’Empire State Building, prima di deporre delicatamente Ann sul cornicione e di precipitare nel vuoto. E mentre Kong spira, ucciso dalla bellezza (come chiosa Carl Denham), Ann è già tra le braccia di Jack, indugiando in tiepidi sospiri: la selezione sessuale ha vinto anche questa volta!

Pietro Lo Cascio

Bibliografia e Sitografia

Busk G. 1867, Description of the remains of three extinct species of elephant, collected by Capt. Spratt, C.B.R.N., in the ossiferous cavern of Zebug, in the island of Malta, Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 6: 227-306.

Darwin C.R. 1871, The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex, J. Murray, London.

Darwin C.R. 1872, The expression of emotions in man and animals, J. Murray, London.

Foster J. 1964, The evolution of mammals on islands, Nature 202: 234-235

Lo Cascio P. 2013, Alfred Russel Wallace e le isole, Naturalista siciliano 37: 645-661.

Rosen D. 2012, The Movie-Star Komodo Dragons that inspired “King Kong”.

Wallace A.R. 1880, Island Life: or the phenomena and causes of insular floras and faunas, including a revision and attempted solution of the problem of geological climates, MacMillan & Co., London.

King Kong claims evolutionism?

“Perhaps King Kong suffers both for its spectacular modesty and the objective limits of its artistry when undergoes to sociological, psychoanalytic, ideological and political interpretations. But certainly the subversive power of the big monkey as a model of otherness compared to the American society of 1930s and, more generally, to its social and moral customs, is still winning”.

So wrote the critic Gianni Rondolino on La Stampa (14 February 1993), examining the implications of the famous film shot in 1933. Probably he has hit the target more than expected.

The story is well known, and has been revived more or less faithfully in the remakes of 1976 and 2005. But highlighting just the elements that characterize King Kong in a biological perspective, we could summarize three main points:

a remote island, a giant ape, and the passion he has for the blonde representative of a different species (the unlucky starlet Ann Darrow).

Through these points, the “subversive power” of the giant gorilla conceived by Merian Cooper and Ernest Shoedsack seems to undermine the anti-evolutionary prejudices typical of the American society at that time, and, unfortunately, still widespread.

All these points, in fact, sound like the echo of the intense intellectual and scientific challenge that, especially during the second half of the 19th century, approached eminent biologists to the study of the islands, as model for understanding the complex mechanisms of evolution of the living organisms.

Islands naturalists, by definition, were Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace: Darwin, among many topics included in the “Origin of Species”, meditated for a long time on the impressions obtained during a visit to the Galápagos; while Wallace stated the occurrence of a relationship between the diversity of life and the selection when he was in struggle for survival at Ternate, in the Moluccas archipelago. Especially Wallace deserved great attention to the theme of insularity through the publication in 1880 of his the fundamental book “Island Life”.

Thanks to the work of Darwin, Wallace and other evolutionists (Hooker, Huxley, Lyell, Gray), it was possible to highlight the role of “refuge” absolved by the islands, where fauna and flora may survive undisturbed, while disappeared elsewhere due to competition and extinction processes.

Examples would be infinite: the tuataras (Sphenodon), true “living fossils” found only in some small satellites of the two major islands of New Zealand; the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), a carnivorous marsupial disappeared thousands of years ago from Australia but still occurring in Tasmania until the 1930s; or, not far from us, the Aeolian Wall Lizard (Podarcis raffonei), a relict species that inhabits a small number of islets, and replaced by the Italian Wall lizard in the larger Aeolian Islands.

On Skull Island, where Carl Denham, Ann and their entourage landed, the tropical fog hides, not only the hairy protagonist of the film, but also a long series of ferocious stegosaurus, tyrannosaurus, elasmosaurus, last survivors of the great mass extinction occurred about 60 million years ago.

Also the size of King Kong seems to be suggested by the studies on the insularity and their peculiar biological and evolutionary phenomenas. While the definition of island rule will be formalized by Foster only in 1964, the fact that many species in the islands show the curious tendency to “reverse” the size (small ones become large, and vice versa) was well known since long time.

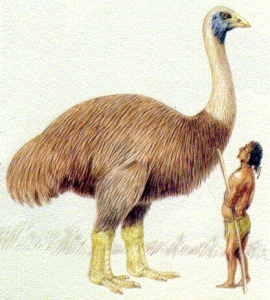

In 1867, the paleontologist George Busk described as Elephas falconeri the dwarf elephants that inhabited Malta, Sicily and other Mediterranean islands until few thousand years ago, which represent one of the most significant examples of insular dwarfism. In the same period were also studied the remains of giant birds like the moa (Dinornithidae) from New Zealand, or Aepyornis maximus from Madagascar, which reached impressive sizes (up to 3 meters high) and that – along with the tortoises of the Galapagos and other islands in the Indian Ocean – are the most famous examples of island gigantism.

According to the Foster’s “rule”, King Kong should have been a dwarf monkey, but that’s life.

The idea of a giant ape, apparently, was suggested to Cooper by the arrival in the Bronx Zoo of two Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis), captured by William Douglas Burden during a mission in the Sunda Islands, as well as by the tales of the same Burden, who during this dangerous expedition was accompanied by his wife.

As the giant lizard was poorly expressive for the movie, Cooper preferred an animal more closely related to our species: the ape. Who else would have been able, indeed to make credible the passion for the blonde Ann, if not someone whose expressions are not much different from what we could have expected to find in the eyes and in the face of a suitor?

Even in this case, should be noted that the combination ape-man was “duty paid” many years before the film; we could go back to 1871, when Charles Darwin published “The Descent of Man” and, for the first time, clearly deals with the evolutionary relationships between humans and their closest cousins. Darwin’s hypothesis will be improved by the subsequent publication of “The expression of emotions in man and animals”, but the English scientist was already become the target of arrows from those who have recognized in the “descent from apes” a strong attack against the religious dogma. It is the beginning of a long conflict between Darwinists and anti-Darwinists, which has reach the present and, very often, overcomes the boundaries of the scientific debate.

Who knows what Darwin would have thought in front of the scene where King Kong gives languid glances at his blonde prey, or where he tries to undress her, intrigued by her pale skin or, probably, by his looks unusually hairless. For the great ape, Ann is not a toy, a trinket to adorn his cave: Kong fights for her as a romantic hero driven by a breath of love, or rather – considering that he is an ape – from uncontrollable erotic drive, although not translatable – for obvious reasons – into something different from the contemplation.

The fact that an archaic monkey is so attracted by a Hollywood starlet appears as an implicit admission of the modest distance, in phylogenetic terms, that separates the two species; somehow, seems to allude to a common denominator, or evoke a shared ancestor.

However, this so explicit admission in a cinematographic work realized in the America of the thirties is rather surprising.

In 1925, the Tennessee Butler Act had banned the teaching of evolutionary theory of Darwin from the public schools in the United States; the evolution will come back in the textbooks only in 1958, but currently, due to the Louisiana Science Education Act of 2008, the school programs should treat it giving equal access to creationism, and so, including also denialist positions on topics such as the anthropic influence in the global warming.

Except for a small elite engaged in the advancement of scientific knowledge, most of the Americans believe that evolution is a devil’s artifact: according to a pool carried out by Gallup in 2012, 46% of Americans believe that man has been created by a divine intervention around 10,000 years ago. Only 5% of the supporters of the Republican Party believes that evolution occurred without the guidance of god, while the percentage rises to 19% among the Democratic supporters: a very poor consolation.

This worrying snapshot regards the country commonly referred as the most advanced at global level in terms of technology and science, where however a large mass followed to ignore – or even rejects strongly – a fundament of the modern thinking: the evolution.

We may therefore conclude that King Kong evokes some fundamentals of scientific findings that support the Darwinist theory, which anyway seem to have been assimilated – and returned to the public – in a unconscious manner. His “subversive power” was not fully grasped, and therefore the film was able to overcome harmless the severe judgment of creationists, always active to defend the dogma from the attacks of the scientific evidences. In this case, the attack is given in the guise of an ape: a nightmare finally killed by the brave airmen after he climbs on the Empire State Building and gently lays the beautiful Ann on the ledge. But when Kong dies, killed by the beauty, Ann is already in the arms of Jack, lingering in amorous sighs: sexual selection won!

Pietro Lo Cascio